‘Getting off the beaten track’ is an often overused phrase, but it’s entirely apt if you’re hoping to explore the less-visited towns and cities across Portugal. Sometimes your destination is the goal; occasionally it’s a bonus, as it can be more about the journey itself and the evolving landscapes the carriage windows frame so perfectly. With this in mind, we give you our pick of Portugal’s Best Railway Journeys…

The Linha do Douro is consistently voted one of the top ten train routes in Europe.

The Linha do Douro is consistently voted one of the top ten train routes in Europe.

Departing from one of Porto’s famous architectural landmarks, the Sao Bento train station, the first hour of your journey takes you northwest, through commuter towns such as Ermeside and Penafiel. These gradually fade away, replaced by rustic villages and isolated olive farms. The views are magnificent as the railway snakes its way upriver to Pinhao, overlooked by an iron-beamed Gustave Eiffel-designed bridge. This sleepy hamlet is arguably the true centre of the port industry. Barrels of new wine were once loaded onto Rabelo boats here, for transportation to the port houses in Gaia. The train took over in the early 1900s, but has since been superseded by road tankers.

The latter section of the line, from Pinhao to its current end at Pocinho, is certainly the most-rugged and remote, passing by the Barragem de Valeira Dam and hydroelectric power station, the narrow Cachao da Valeira river gorge, and over the Ponte Ferradosa bridge. The line continues a further 28km beyond Pocinho to the border, but services on the Spanish side were discontinued in 1984. There’s talk of the reinstating 30km of the line from here to Barca d’Alva, and perhaps one day a high-speed link between Lisbon and Madrid.

The latter section of the line, from Pinhao to its current end at Pocinho, is certainly the most-rugged and remote, passing by the Barragem de Valeira Dam and hydroelectric power station, the narrow Cachao da Valeira river gorge, and over the Ponte Ferradosa bridge. The line continues a further 28km beyond Pocinho to the border, but services on the Spanish side were discontinued in 1984. There’s talk of the reinstating 30km of the line from here to Barca d’Alva, and perhaps one day a high-speed link between Lisbon and Madrid.

You could view the Douro Valley line as neglected or forgotten by Comboios de Portugal (the state-owned railway operator). However, the lack of modernisation is one of its many charms. Trains usually have just three or four carriages: the red/white and blue/white carriages are Swiss and Austrian in origin; their windows open fully so give you the best views and opportunities for photographs. There’s usually a silver carriage at the front of the train, just behind the locomotive. They’re our favourites; Portuguese built with a mix of seventies-meets-art-deco.

You could view the Douro Valley line as neglected or forgotten by Comboios de Portugal (the state-owned railway operator). However, the lack of modernisation is one of its many charms. Trains usually have just three or four carriages: the red/white and blue/white carriages are Swiss and Austrian in origin; their windows open fully so give you the best views and opportunities for photographs. There’s usually a silver carriage at the front of the train, just behind the locomotive. They’re our favourites; Portuguese built with a mix of seventies-meets-art-deco.

There’s no buffet car or food/drink service, so I’d recommend stocking up on supplies before you head to the station. I’d also recommend sitting on the right-hand side of the train for the best views, but be ready to close your window as you head into the tunnels to avoid the exhaust fumes from the locomotive. The Class 1400 diesel locomotive at the front of the train was built by English Electric and Vulcan Foundry in the late 1960s, based on the design of the British Rail Class 20. Most of the old diesel fleet has been retired or demoted to freight work as the Portuguese rail network has been electrified – it’s only really here on the Douro line where they’re still used for passenger services.

Day trips on the Linho do Douro are possible from Porto and Vila Nova da Gaia, but to enjoy the whole line at a more leisurely pace, we recommend our Porto and Douro Valley by Train holiday.

The Fertagus Line is an anomalous part of the Portuguese railway network.

The Fertagus Line is an anomalous part of the Portuguese railway network.

Originally known as the Eixo Norte-Sul (North-South Axis), this is currently the online privately run passenger line in the country, connecting the Areeiro district of the capital Lisbon to the old ship building of Setubal. It’s primarily a commuter line and not much to write about on paper. However, it does gives you a unique perspective on two of the capital’s most-impressive man-made landmarks.

The first is the Aqueduto das Aguas Livres which dominates the skyline over Campolide station. Built in 1744 to bring much-needed fresh water into the city from the parish of Canecas, the aqueduct consist of thirty-five arches spanning a total distance of 941m, feeding water into an underground the Reservatório da Mae d’Agua das Amoreiras in the centre of the city. Testament to their over-engineered design and construction, both structures survived the great earthquake of 1755. However, they didn’t survive the construction of the Barbadinhos reservoir which superseded them – both the aqueduct and the Mae d’Agua were decommissioned in 1968.

The Aqueduto das Aguas Livres will live in infamy, thanks to serial killer Diogo Alves. Known as the Aqueduct Murderer, Diogo attacked and robbed seventy passers by in the mid-1800s, throwing them off the 65m high aqueduct in order to disguise his crimes as suicides. Tried and convicted in 1841, Alves was the penultimate criminal to be hanged in Portugal, but his tale took an even more macabre twist. After his death, his head was preserved and donated to Lisbon’s surgical school: perhaps an early example of neuro-criminology, the head still exists in a glass jar of formaldehyde at Lisbon University and can be viewed by appointment.

The Aqueduto das Aguas Livres will live in infamy, thanks to serial killer Diogo Alves. Known as the Aqueduct Murderer, Diogo attacked and robbed seventy passers by in the mid-1800s, throwing them off the 65m high aqueduct in order to disguise his crimes as suicides. Tried and convicted in 1841, Alves was the penultimate criminal to be hanged in Portugal, but his tale took an even more macabre twist. After his death, his head was preserved and donated to Lisbon’s surgical school: perhaps an early example of neuro-criminology, the head still exists in a glass jar of formaldehyde at Lisbon University and can be viewed by appointment.

Without doubt the highlight of this train journey is the crossing of the magnificent Ponte 25 de Avril bridge. This 2.3km suspension bridge was constructed in 1966 and was originally christened the ‘Ponte Salazar’ – named after Prime Minister Antonio Salazar, leader of the ruling fascist Estado Novo regime. This dark period in the nation’s history saw Europe’s great explorers retreat inwards, as the Salazar regime suppressed outside influences and free speech. A group of middle-ranking army officers, (the ‘April Captains’, as they became known), co-ordinated a military coup on 25th April 1974 by transmitting the song ‘Grandola, Vila Morena’ by Jose Afonso – the transmission instigated a series of synchronised takeovers at key institutions across the city. The Lisboetas took to the streets en-masse, and the government relinquished power six hours later. As a lasting symbol of their ‘Carnation Revolution’, the citizens marched across the bridge, forcibly removed Salazar’s plaque and painted ’25 de Abril’ in its place.

Without doubt the highlight of this train journey is the crossing of the magnificent Ponte 25 de Avril bridge. This 2.3km suspension bridge was constructed in 1966 and was originally christened the ‘Ponte Salazar’ – named after Prime Minister Antonio Salazar, leader of the ruling fascist Estado Novo regime. This dark period in the nation’s history saw Europe’s great explorers retreat inwards, as the Salazar regime suppressed outside influences and free speech. A group of middle-ranking army officers, (the ‘April Captains’, as they became known), co-ordinated a military coup on 25th April 1974 by transmitting the song ‘Grandola, Vila Morena’ by Jose Afonso – the transmission instigated a series of synchronised takeovers at key institutions across the city. The Lisboetas took to the streets en-masse, and the government relinquished power six hours later. As a lasting symbol of their ‘Carnation Revolution’, the citizens marched across the bridge, forcibly removed Salazar’s plaque and painted ’25 de Abril’ in its place.

Uniquely for the Portuguese rail network, the Fertagus Line’s electric multiple units are double decker, and sitting on the top deck is a must for the best view as you cross the Tagus River. The river pops up as a natural divide throughout Portuguese history, and it’s quite surprising that the first bridge wasn’t built until 1966. The rail platform came even later – it was added as part of a major refurbishment in 1999.

Uniquely for the Portuguese rail network, the Fertagus Line’s electric multiple units are double decker, and sitting on the top deck is a must for the best view as you cross the Tagus River. The river pops up as a natural divide throughout Portuguese history, and it’s quite surprising that the first bridge wasn’t built until 1966. The rail platform came even later – it was added as part of a major refurbishment in 1999.

A second bridge, the Vasco da Gama road bridge, was constructed in 1998 – this 12km bridge was once Europe’s longest bridge until the opening of the Crimean Bridge in 2018. Future plans are being mooted for an extension of the Lisbon Metro under the river, to connect the city with the beaches of the Costa da Caparica on the southbank, a third bridge from Chelas to Barreiro, and possibly a road tunnel from Alcochete to the site of the new airport.

A second bridge, the Vasco da Gama road bridge, was constructed in 1998 – this 12km bridge was once Europe’s longest bridge until the opening of the Crimean Bridge in 2018. Future plans are being mooted for an extension of the Lisbon Metro under the river, to connect the city with the beaches of the Costa da Caparica on the southbank, a third bridge from Chelas to Barreiro, and possibly a road tunnel from Alcochete to the site of the new airport.

Back on the train, you could alight at Pragal to visit one of Lisbon’s most-photographed landmarks: the Santuario de Cristo Rei catholic monument. Although it’s often compared to the more famous statue in Rio, its design was inspired by a much older monument on the island of Madeira. The Cais do Sodre ferry criss-crosses the river throughout the day (departing every fifteen minutes), and it normally takes around thirty minutes to walk up the hill from the ferry terminal the Santuario. You can take a lift (for 5€ per person) up to the viewing platform on statue’s giant plinth for a 360⁰C view of Lisbon’s endless waterfront, the Serra de Sintra to the east and the green hills of the Serra de Arrabida to the south.

Back on the train, you could alight at Pragal to visit one of Lisbon’s most-photographed landmarks: the Santuario de Cristo Rei catholic monument. Although it’s often compared to the more famous statue in Rio, its design was inspired by a much older monument on the island of Madeira. The Cais do Sodre ferry criss-crosses the river throughout the day (departing every fifteen minutes), and it normally takes around thirty minutes to walk up the hill from the ferry terminal the Santuario. You can take a lift (for 5€ per person) up to the viewing platform on statue’s giant plinth for a 360⁰C view of Lisbon’s endless waterfront, the Serra de Sintra to the east and the green hills of the Serra de Arrabida to the south.

Riding the Fertagus Line to its conclusion will bring you to Setubal. Setubal is popular with the residents of Lisbon for its fresh fish, particularly a dish called choco frito. Like so many great recipes, it’s a dish born out of necessity: cuttle fish was seen as poor man’s squid and local fishermen struggled to sell their catches. The fish would end up being traded for beer and wine with local bar keepers – they’d simmer the fish in saltwater with bay and garlic, before dusting them in cornflower and deep frying them. The resultant choco frito were served back to the fishermen as late-night bar snacks – it’s now a staple of restaurant menus across the town and a fabulous end to the train journey.

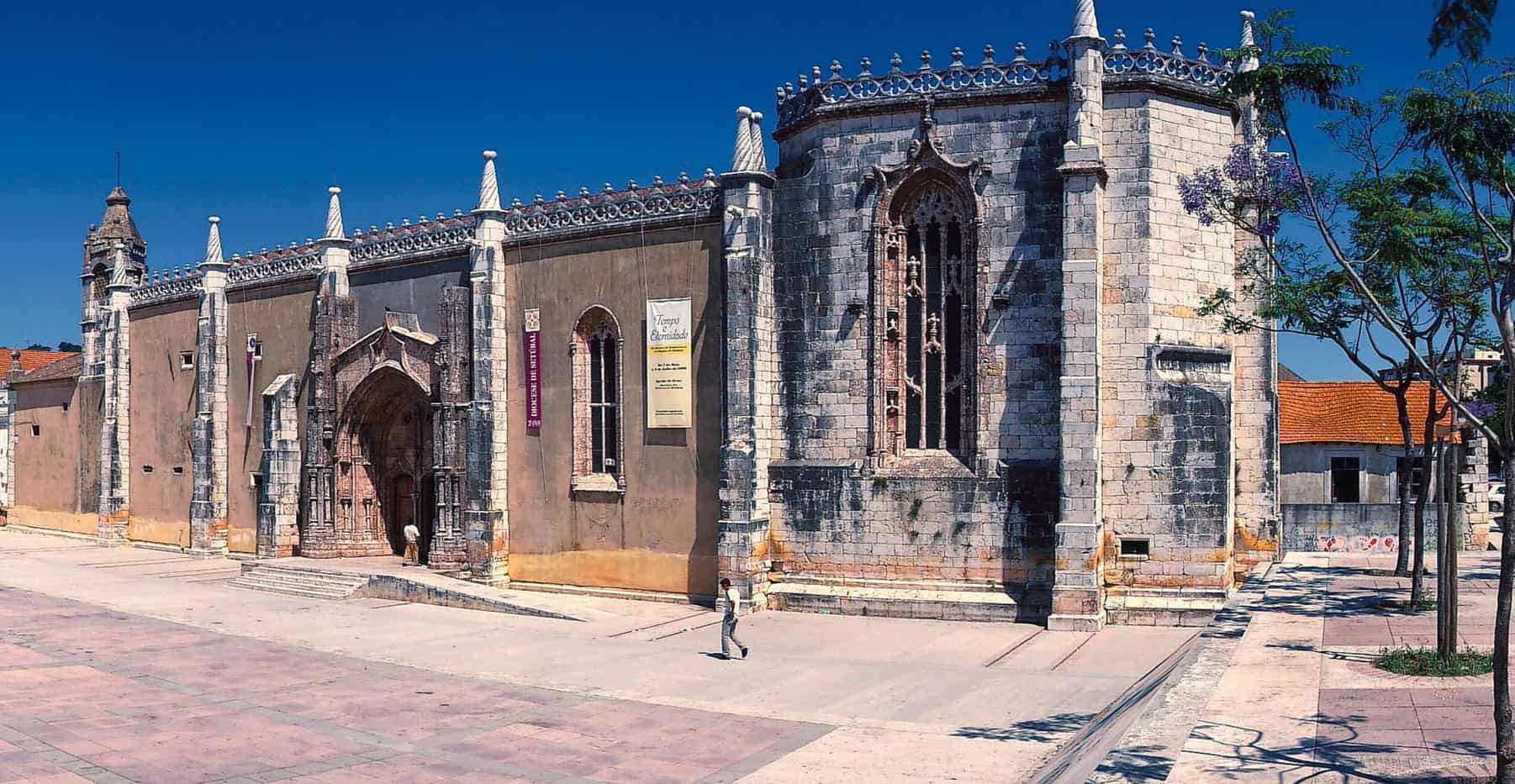

Thanks to its location on the Sado estuary, Setubal was one of Portugal’s largest industrial centres and home to the Lisnave shipyards – it’s been sadly neglected in recent years, but its historic centre around the Convento de Jesus, the Museu de Setubal and the Ingeja do Antigo Mosteiro de Jesus (with its impressive spiralling Solomonic columns) has seen recent renovation.

Fertagus Line trains depart every thirty minutes from Lisbon’s Roma-Areeiro station, arriving into Setubal roughly an hour later. Train run from just before 6:00am to midnight, and tickets can be booked via the Fertagus website.

Fertagus Line trains depart every thirty minutes from Lisbon’s Roma-Areeiro station, arriving into Setubal roughly an hour later. Train run from just before 6:00am to midnight, and tickets can be booked via the Fertagus website.

The Linha de Sintra connects the capital Lisbon with the charming hilltop town of Sintra.

The Linha de Sintra connects the capital Lisbon with the charming hilltop town of Sintra.

The line had quite a sketchy birth: a number of different projects were proposed and cancelled between 1854 and 1887, until the first line was constructed from Alcantara-Terra (just north of the present-day Ponta 25 de Avril) to Sintra. It was quickly extended into the very centre of the in 1889, terminating at the newly constructed Rossio Station. The Estacao de Caminhos de Ferro do Rossio, to give it its full title, was designed by Portuguese architect Jose Luis Monteiro.

Now considered one of Lisbon’s landmark buildings, Monteiro’s intricately detailed front façade, with its ornate horseshoe entrances harked back to the 16th century Manueline architecture more common to the Belem district. Most of the Manueline buildings in the centre of the city were destroyed in the great earthquake of 1755. Montiero’s father was a stone mason, and Jose was trained to work Estremoz marble from an early age – although the budget for the station could only stretch to limestone. The over-extended arches, which form the entrance to the station, are shaped to match the departure and arrival tunnels which take the line west. Look closely above the right-hand door, and you’ll see a bust presenting ‘Father of the Railways’ George Stephenson – and over the left-hand door, Prime Minister Antonio Maria de Fontes Pereira de Melo who was one of the driving forces behind Portuguese railway expansion in the 1800s.

Now considered one of Lisbon’s landmark buildings, Monteiro’s intricately detailed front façade, with its ornate horseshoe entrances harked back to the 16th century Manueline architecture more common to the Belem district. Most of the Manueline buildings in the centre of the city were destroyed in the great earthquake of 1755. Montiero’s father was a stone mason, and Jose was trained to work Estremoz marble from an early age – although the budget for the station could only stretch to limestone. The over-extended arches, which form the entrance to the station, are shaped to match the departure and arrival tunnels which take the line west. Look closely above the right-hand door, and you’ll see a bust presenting ‘Father of the Railways’ George Stephenson – and over the left-hand door, Prime Minister Antonio Maria de Fontes Pereira de Melo who was one of the driving forces behind Portuguese railway expansion in the 1800s.

Entering the station on foot, you’ll find the main concourse is actually the lower level – being spread across seven hills, Lisbon is notoriously undulating, and the platforms and trains are on the upper level, two stores up from street level. To bring the lines into the city, engineers carved two 2.6km tunnels, running from Campolide Station to their high-level terminus here at Rossio. The original wrought iron columns and canopy still provide cover over the platforms. You’ll also see a series of decorative mosaic panels lining the outer walls, celebrating the country’s agricultural history. The panels were commissioned in 1940 as part of the Exposicao do Mundo Portugues: the Portuguese World Exhibition which marked the 800th birthday of the nation. The exhibition was held in the Praca do Imperio, close to the Jeronimos Monastery in Belem, and the panels were relocated to Rossio station when the celebrations ended.

The Linha de Sintra was electrified during the 1950s and the proved to be one of the great success stories of the Portuguese rail network. As the country became better-connected by road and the popularity of the motor car increased, the railways were unfunded and neglected, mothballed, and in many cases, decommissioned. The suburban population to the north and west of Lisbon was growing rapidly, and the Linha de Sintra struggled to keep pace with demand in the late 20th and early 21st century. As a railway journey, the line itself is extremely urban, taking you to the north of Monsanto Park and through the districts of Buraca, Amadora and Massama. Arriving in Sintra can be something of a surprise – just as it’s famous hilltop palace pops into view, the line ducks into an extremely narrow tunnel, before emerging at Sintra station.

A five/ten-minute walk brings you into the pretty centre of the town. Up until the mid-19th century, Sintra was the favoured summer retreat for Portugal’s royal dynasties, as its elevated location provided a cool escape from the heat of central Lisbon. Its centre is dominated by the Palacio Nacional de Sintra – most of the present-day building was constructed by Dom Joao I in the early 1400s, but each subsequent monarch has made his or her mark. Dom Manuel I added the Sala dos Barsoes (the Room of the Coats of Arms) and the palace’s east wing in the late-1400s. The elaborate decoration and intricate detailing is evidence of the wealth which was flowing into Portugal during that time, particularly in the form of gold from its colony in Brazil. The palace’s final occupant was the queen dowager Maria Pia: widow of Dom Luis I and grandmother to Dom Manuel II, the last king of Portugal. Following revolution of 1910 and the establishment of the 1st Republic, the deposed King was exiled to England and lived out his days in Twickenham – Maria Pia left the palace and chose to return to her native Italy, where she died a year later.

A five/ten-minute walk brings you into the pretty centre of the town. Up until the mid-19th century, Sintra was the favoured summer retreat for Portugal’s royal dynasties, as its elevated location provided a cool escape from the heat of central Lisbon. Its centre is dominated by the Palacio Nacional de Sintra – most of the present-day building was constructed by Dom Joao I in the early 1400s, but each subsequent monarch has made his or her mark. Dom Manuel I added the Sala dos Barsoes (the Room of the Coats of Arms) and the palace’s east wing in the late-1400s. The elaborate decoration and intricate detailing is evidence of the wealth which was flowing into Portugal during that time, particularly in the form of gold from its colony in Brazil. The palace’s final occupant was the queen dowager Maria Pia: widow of Dom Luis I and grandmother to Dom Manuel II, the last king of Portugal. Following revolution of 1910 and the establishment of the 1st Republic, the deposed King was exiled to England and lived out his days in Twickenham – Maria Pia left the palace and chose to return to her native Italy, where she died a year later.

Sintra’s most-popular landmark is the colourful Palacio da Pena was commissioned by Queen Dona Maria II at the tail-end of Romanticism in 1854. Inside and out, it’s an eclectic mix of medieval vaulted arches, byzantine domes, Islamic stuccos, and Manueline gothic windows, columns and arcades. The Pena is famously preserved exactly as it was on 4th October 1910, when Dona Maria Amelia, the last queen of Portugal, stayed for her final night before the 1st Republic abolished the monarchy and the royal family fled to Gibraltar. One of our favourite landmarks is the Castelo dos Mouros – the Moorish stronghold dating back to the 8th century. Sintra owes its existence to the castle – it was constructed in the 9th century when the region was under Muslim rule. It fell to the Portuguese shortly after Dom Afonso I’s successful siege of Lisbon in 1147 – Gualdim Pias, a prominent figure in medieval Portugal thanks to his association with the Knights Templar, was granted governorship of a fledging Sintra. As the moors retreated south (and eventually across the Mediterranean), the protection offered by the castle became less important, and the settlement outside the fortified walls expanded quickly as new residents were drawn from across the Tejo floodplains. Sintra was officially granted town status in 1154.

Sintra’s most-popular landmark is the colourful Palacio da Pena was commissioned by Queen Dona Maria II at the tail-end of Romanticism in 1854. Inside and out, it’s an eclectic mix of medieval vaulted arches, byzantine domes, Islamic stuccos, and Manueline gothic windows, columns and arcades. The Pena is famously preserved exactly as it was on 4th October 1910, when Dona Maria Amelia, the last queen of Portugal, stayed for her final night before the 1st Republic abolished the monarchy and the royal family fled to Gibraltar. One of our favourite landmarks is the Castelo dos Mouros – the Moorish stronghold dating back to the 8th century. Sintra owes its existence to the castle – it was constructed in the 9th century when the region was under Muslim rule. It fell to the Portuguese shortly after Dom Afonso I’s successful siege of Lisbon in 1147 – Gualdim Pias, a prominent figure in medieval Portugal thanks to his association with the Knights Templar, was granted governorship of a fledging Sintra. As the moors retreated south (and eventually across the Mediterranean), the protection offered by the castle became less important, and the settlement outside the fortified walls expanded quickly as new residents were drawn from across the Tejo floodplains. Sintra was officially granted town status in 1154.

Due to the popularity of Sintra with daytrippers, Rossio can be an extremely busy station. Wise visitors take an early train in order to avoid the crowds when visiting the palaces – however, as a consequence you could hit the congestion of the station’s morning rush hour. Travel in the afternoon, and services are busy with tourists heading west to visit the Pena Palace. The direct service departs just after the hour and it takes around forty-minutes to complete the journey – there’s also a service just after half-past, which is slightly slower as it involves a connection at Agualva Cacem. Less well-known (at least to visitors): there’s also a direct service from Lisbon’s Oriente station which takes forty-seven minutes to get to Sintra. It’s much quieter route (after the rush hour), and you can always visit Rossio station on your return journey back into the city.

Due to the popularity of Sintra with daytrippers, Rossio can be an extremely busy station. Wise visitors take an early train in order to avoid the crowds when visiting the palaces – however, as a consequence you could hit the congestion of the station’s morning rush hour. Travel in the afternoon, and services are busy with tourists heading west to visit the Pena Palace. The direct service departs just after the hour and it takes around forty-minutes to complete the journey – there’s also a service just after half-past, which is slightly slower as it involves a connection at Agualva Cacem. Less well-known (at least to visitors): there’s also a direct service from Lisbon’s Oriente station which takes forty-seven minutes to get to Sintra. It’s much quieter route (after the rush hour), and you can always visit Rossio station on your return journey back into the city.

We specialise in personalised holidays to Portugal.

Call our team 017687 721070 to begin planning your own personalised trip.

Follow us online